[elfsight_social_share_buttons id=”1″]

Ukraine has asked its international creditors, including Western powers and the world’s largest investment firms, to freeze its debt payments for two years so it can focus its dwindling financial resources on repelling Russia.

Facing an estimated 35% to 45% crash in GDP this year following Moscow’s invasion in February, Ukraine’s finance ministry said on Wednesday it was hoping to finalize the deferral on its roughly $20 billion of debt by Aug. 9.

The delay, which was quickly backed by both the major Western governments and heavyweight funds that have lent to Kyiv, would come just in time to put off around $1.2 billion of debt payments due at the start of September.

The government’s proposal, posted on its website, said all its bond interest payments would be deferred under the plan, although to avoid what would be classed as a hard default it also offered lenders additional interest payments once the freeze ends.

“The disruption to fiscal cash flows and increased demands on government resources caused by the war has created unprecedented liquidity pressures and debt servicing difficulties,” the finance ministry said.

It came amid signs that Moscow is now stepping up its assault, with Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov saying on Wednesday that the Kremlin’s military objectives in Ukraine now go beyond the eastern Donbas region.

Ukraine has estimated that the cost of the war combined with lower tax revenues have left a $5 billion-a-month fiscal shortfall – or 2.5% of pre-war GDP. Economists calculate that pushes the annual deficit to 25% of GDP, compared with just 3.5% before the conflict.

On top of that, researchers from the Kyiv School of Economics estimate that it will already take over $100 billion to rebuild Ukraine’s bombed infrastructure, while the head of the EU’s powerful financing arm, the European Investment Bank, has warned it could run into trillions.

It is estimated that the debt freeze could save Ukraine around $5 billion over the deferral period.

“We, as official bilateral creditors of Ukraine, intend to provide a coordinated suspension of debt service,” a group of governments including the United States, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and Britain said shortly after Ukraine made its proposal.

“We also strongly encourage all other official bilateral creditors to swiftly reach agreement” the group added.

‘Explicit indications of support’

Ukraine’s finance minister, Sergii Marchenko, said in a statement that the plan had also received “explicit indications of support” from some of the world’s biggest investment funds including BlackRock, Fidelity, Amia Capital, and Gemsstock.

Wednesday’s move had marked something of a U-turn from Kyiv, which had repeatedly said in recent months that it planned to keep up debt payments despite the war.

Speculation that a debt freeze request could be imminent however was fanned last week after the country’s state-run energy firm Naftogaz also requested one.

“A proper restructuring still needs to happen,” said Viktor Szabo, a portfolio manager at abrdn which holds Ukraine’s government bonds. “But it cannot be done before the situation normalizes on the ground, i.e. a sustained cease-fire at least.”

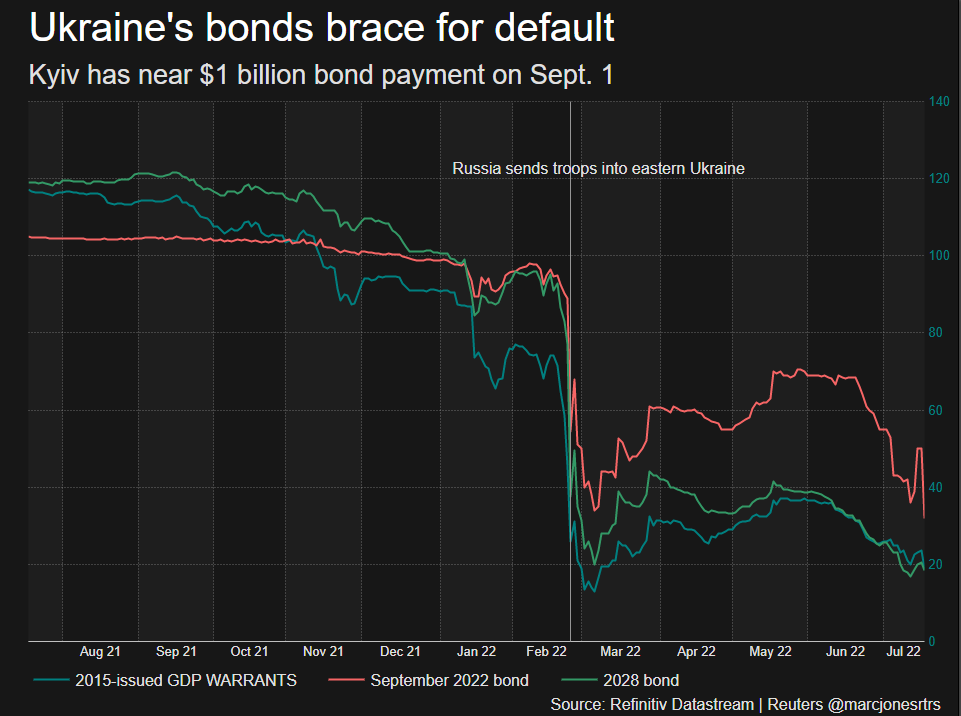

Ukraine has a host of bonds which add up to over $20 billion of borrowings. The government also plans to postpone payment on a growth-linked ‘warrant’ offered after its last restructuring in 2015, which was designed to pay investors handsomely if the economy hit its stride.

Tymofiy Mylovanov, an adviser to the Ukrainian presidential office, had urged Western countries to increase their financial support in recent weeks.

Global institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and Western governments have committed to providing $38 billion since the invasion, although almost 80% of that support is made up of loans rather than aid.

Through a spokesperson, the IMF said “in general, voluntary pre-emptive agreements would be a net positive for the outlook.”

Last week the Fund said international community grant financing was a priority for Ukraine’s immediate and short-term, as that would allow the government to remain operational without incurring further debt.

Wednesday’s move had little impact on Ukraine’s bonds, most of which had already slumped more than 80% since Russia began building up its troops on Ukraine’s borders late last year.

“There is quite a bit of support in the market to agree to this,” said Petar Atanasov, the co-head of sovereign research at specialist distressed debt fund Gramercy.

“Unfortunately, there are no signs of peace or a cease-fire on the horizon.”