[elfsight_social_share_buttons id=”1″]

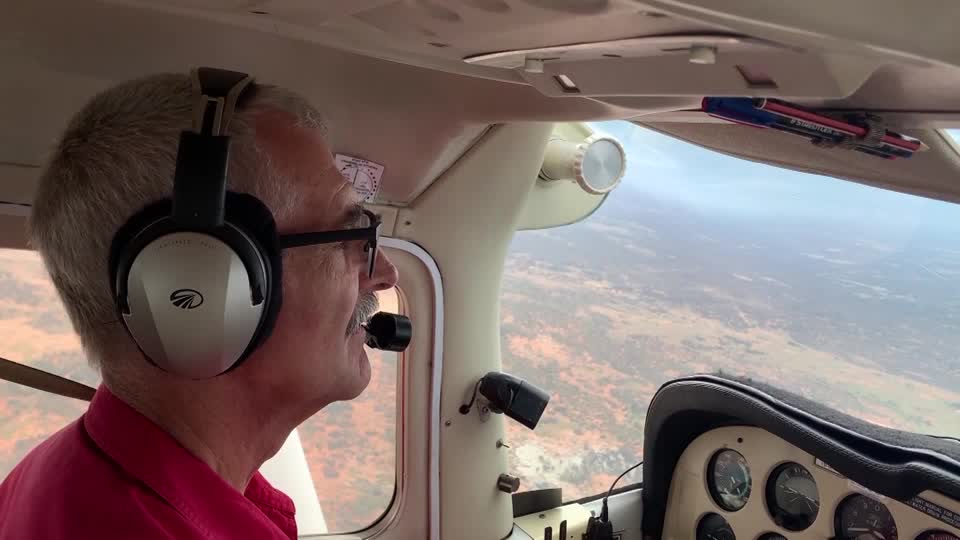

During the Australian outback summer, Christmas spirit does not travel by sleigh. It wings in on a single-engine Cessna 182.

At least, that is how David Shrimpton, a pastor with a pilot’s license, delivers holiday cheer to a congregation of a couple of thousand spread over livestock and farmland nearly three times the size of Ireland. Since 2003 the Uniting Church pastor has been flying to some of Australia’s most isolated communities to talk and listen to a scattered flock.

That largely stopped last year when Australia introduced some of the world’s strictest COVID-19 restrictions. “Padre Dave” could have claimed essential worker status and kept his schedule of four visits a year throughout this 87,000 sq mile region, but he opted for phone catchups to minimize the risk of spreading the coronavirus.

Now, with restrictions easing, Shrimpton is taking to the skies again with hopes of sharing the closest thing to a normal Christmas season this vast tract of western New South Wales state has seen in years. Graziers, farmers, school children, churchgoers, non-believers, all are on Shrimpton’s agenda.

“It will be great to go out again and reconnect with these folk, reconnect with the kids and be part of their school life once again, reconnect with the adults who are living remotely and, let them know that they’re not forgotten,” Shrimpton, 57, told Reuters at a small airport near his home in Broken Hill.

“Some had thought that I’d retired and moved on, but no, I’m still here and still willing to go out and catch up.”

The pandemic was just the latest in a string of setbacks – after nearly a half decade of drought – for this loose network of one-pub towns, sheep and cattle stations, Indigenous communities and schools with a handful of children.

“A lot of these blokes out here are big and tough, but they have a soft side and the drought buckled a few,” said Josh Sheard, a former pub owner who has put up Shrimpton for years in Pooncarie, where a sign outside the town says, “Population 84”.

Locals will tell you it’s far fewer now.

“To be able to talk to Dave was really good for them. They only like telling each other what they’re doing when they’re making money,” said Sheard.

Sara Carey, who looks after a merino sheep operation called Netley Station with her partner Tony, has had visits from Shrimpton for six years. Shrimpton, she said, has a knack for getting men to “have a cup of tea and … answer questions they don’t even realize they’re answering.”

Pooncarie’s five public school students – who don’t have internet connections good enough for home learning or socializing during lockdowns – were excited about their year-end awards day mostly because of who would be attending.

“Even though they knew they were going to get a disco, they knew they were going to get awards, they were putting on a play, all they talked about the last few days was ‘when’s Padre Dave coming?'” said Alison King, the school’s teaching principal.

“It’s about having someone to just spend time with, and if they’ve got any concerns they can talk to him, even if it’s just to talk, having someone just to listen. He comes and listens.”

Shrimpton’s unusual occupation is the result of two callings. He was interested in flying as a child, he said, but worked in real estate and childcare and drove taxis before studying, at his wife’s urging, to become a minister.

While appointed to a church near an airport, he happened to see an advertisement for flying lessons and signed up on a whim. Next thing, he was moved to Darwin, another remote location in northern Australia, to begin what has become nearly 20 years as a flying pastor. He moved to Broken Hill in 2014.

Shrimpton said that like his congregation, he also has been impacted by the restrictions imposed on social interaction over the past two years. This visit would mark the beginning of “better times and a brighter future”, he said.

“It’s time to celebrate … enjoying one another’s company and hearing from folk in the bush that they are looking forward to connection with family that wasn’t there last Christmas.”

(Reporting by Loren Elliott; Writing by Byron Kaye; Editing by Tom Hogue)

Copyright 2021 Thomson/Reuters